February 21, 2026

Remember when pouring money into AI was like owning a printing press for stock market value? Those were the days—specifically, about six weeks ago. Since then, the world’s most exalted technology companies have engaged in a collective market capitalization reduction program so aggressive it would make a Victorian corset-maker blush .

Let’s take a moment to appreciate the sheer scale of the value that has vaporized. In just the first six weeks of 2026, the combined market cap of Apple, Microsoft, Alphabet, Amazon, and Nvidia has shriveled by $1.3 trillion . To put that in perspective, that’s roughly the GDP of Spain—evaporated because investors suddenly realized that spending billions on something that can’t consistently tell you whether you need an umbrella might not be the soundest business strategy .

The “Trust Us, We’re Spending Heavily” Business Model

For years, the pitch was beautifully simple: “We’re investing massively in AI infrastructure. Look at our capital expenditures! Surely that must mean something!” And for a while, it worked. Investors nodded sagely as companies burned cash on GPU clusters the size of small cities, comforted by the knowledge that if you throw enough money at a problem, it eventually becomes a moat .

Then came 2026, and with it, a truly terrifying development: investors started asking to see actual profits . The horror. The audacity.

Microsoft, which has been telling the AI origin story so effectively that people forgot they’re primarily a software licensing company, has seen its stock tumble 17% this year—a $613 billion haircut that brings its valuation down to a still-bloated $2.98 trillion . The problem? Competition from Google’s Gemini and Anthropic’s Claude Cowork, which are apparently good enough that customers are questioning why they need Microsoft’s version of everything .

Amazon isn’t faring much better, down 13.85% with $343 billion in market value gone . The company announced that capital investment would surge 50% this year, and investors responded in exactly the way you’d expect when someone tells you they’re going to spend even more money on something that hasn’t paid off yet .

The Depreciation Situation: Accounting’s Finest Comedy

Perhaps the most delightful subplot in this drama involves Michael Burry—yes, the “Big Short” guy—pointing out that AI companies have been playing games with depreciation that would make an Enron accountant blush .

Here’s the joke: Nvidia releases new GPUs every 12 to 18 months. The Blackwell chips from 2024 are already being shown the door by the Rubin chips arriving later this year, which offer triple the performance . So you’d think these expensive pieces of silicon would be depreciated over, say, two to three years—their actual useful life before they’re obsolete.

But no. Some companies have been stretching that to five or six years in their accounting, because why let reality interfere with earnings reports? Burry estimates this little accounting magic trick has inflated industry earnings by a collective $176 billion between 2026 and 2028 . Meta alone reduced its 2025 depreciation expense by $2.9 billion by simply deciding its servers would last longer . It’s like claiming your 2019 iPhone is still worth what you paid for it because “it technically turns on.”

The Efficiency Paradox: You Made It Too Cheap, You Fools

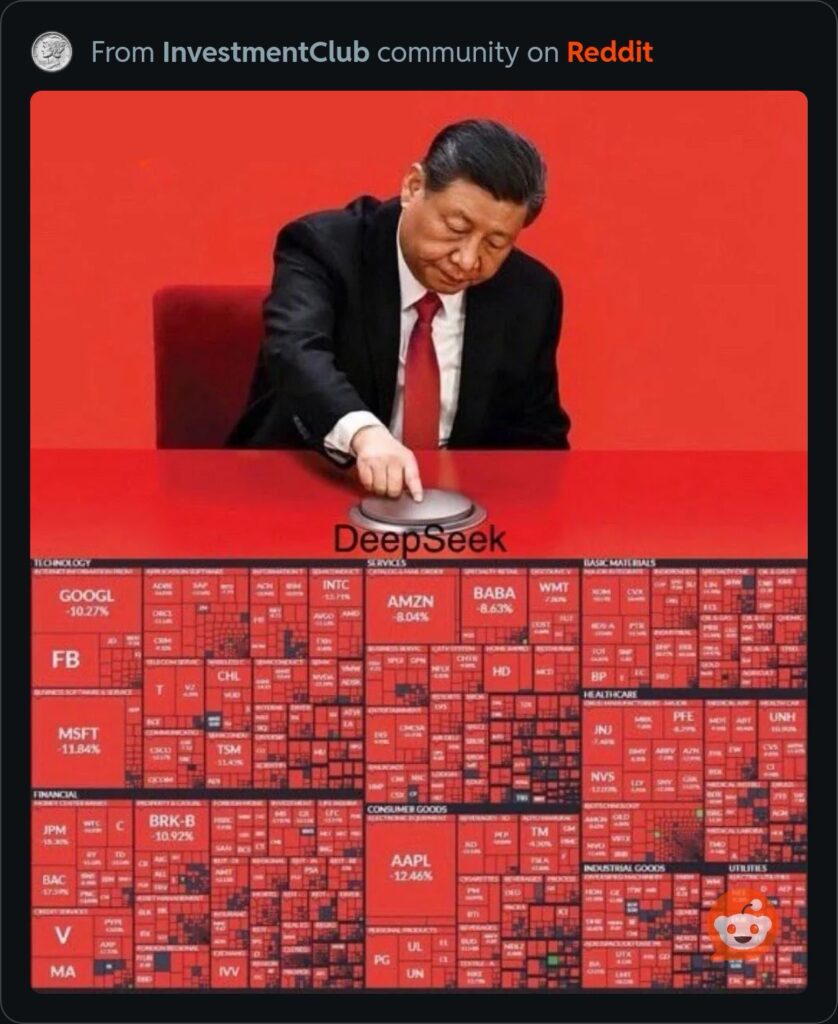

While the giants were busy building ever-larger models that required ever-more-expensive compute, something embarrassing happened in the background. DeepSeek and its ilk demonstrated that you could actually run AI models for pennies .

The cost of processing a million tokens has fallen approximately 90% in a year. Inference costs have dropped from “cents” to “micro-cents” . When DeepSeek R1 arrived in early 2025, it wasn’t just another model—it was the moment the “compute is everything” thesis started looking like a hot air balloon with a slow leak .

For the hyperscalers who bet everything on being the exclusive landlords of the AI compute empire, this was awkward. It’s like building a network of luxury toll roads only to discover that someone invented teleportation and people are using it for free.

The SaaS Massacre: When Your Subscription Model Meets a Single AI Prompt

Perhaps nowhere is the carnage more visible than in the software sector, where the traditional SaaS model is experiencing what can only be described as a public execution .

The culprit? Something called OpenClaw and similar “AI-native clouds” that let a single developer with a good idea and a laptop replace what used to require a 50-person company . Why pay for separate Salesforce, DocuSign, and Intuit subscriptions when an AI agent can just… do all of those things in an integrated workflow?

The market’s response has been swift. The S&P North American Software Index dropped 15% in a month. Thomson Reuters fell 16% in a single day. DocuSign is down nearly 30% year-to-date . These companies spent decades building moats around specific functions, only to discover that AI doesn’t respect moats—it just bridges them and collects the toll on the other side.

The One-Person Company and Other Existential Threats

Here’s where it gets genuinely funny. In the old world, if you wanted to compete with a giant software company, you needed venture capital, a team of engineers, a sales force, and about five years of runway .

In the 2026 world, you need a laptop, a coffee subscription, and the ability to describe what you want to an AI that writes the code, deploys the product, handles customer service, and runs the marketing . Silicon Valley is now watching “one-person companies” disrupt verticals that took incumbents decades to build. The development cycle has gone from months to days. The cost structure has gone from millions to “whatever my AWS bill is this month” .

And what are the giants doing about this? They’re building their own AI agents, of course. Microsoft has Operator. Anthropic has Claude Cowork. Everyone has something that’s supposed to replace the very software they’ve been selling for the last twenty years . It’s like watching a car company pivot to selling really excellent horse blinders just as the Model T rolls off the assembly line.

The Bright Spots: Chips and Cheap Stuff

If you’re looking for winners in this environment, look no further than the companies that actually make the stuff, rather than the ones that just rent it out. TSMC’s market cap has increased by $294 billion this year . Samsung Electronics is up $273 billion . Walmart—yes, the store where you buy toothpaste—has added $179 billion in value .

The message from the market couldn’t be clearer: we’d rather own the company that manufactures the shovels for the gold rush, or better yet, the company that sells affordable socks to the people who didn’t find gold.

What Actually Happened?

If we’re being honest—and at this point, why wouldn’t we be, given that $1.3 trillion has already vanished?—the AI industry just experienced the gap between “vision” and “business model” finally snapping shut .

For years, the thesis was that if you built massive models with massive compute and massive data centers, the profits would eventually materialize. It worked for search. It worked for social media. It worked for e-commerce. Why wouldn’t it work for AI?

Because AI has a cost structure that looks more like 20th-century heavy industry than 21st-century software . Every query costs money. Every user adds expense. Scale doesn’t reduce marginal costs—it multiplies them. And when you combine that with competition that’s driving prices toward zero, you have a recipe for what analysts are now calling “margin compression” and what normal people would call “spending a lot to make a little” .

The Future: Smaller Models, Smaller Ambitions, Smaller Valuations

So where do we go from here? The industry is rapidly discovering that bigger isn’t better—it’s just more expensive. The new mantra is efficiency, optimization, and actually solving problems that people will pay for .

The model providers are becoming infrastructure, which is a polite way of saying they’re becoming utilities with utility company valuations. The real action is in applications, agents, and the messy business of making AI do useful things in specific contexts .

And for the workers who spent 2025 frantically learning prompt engineering and the latest frameworks? Well, those skills now have a half-life measured in months rather than years . The AI that writes code also writes better prompts, which means the prompt engineer is about as relevant as a COBOL programmer at a blockchain conference.

The Bottom Line

The great AI market cap reduction of 2026 isn’t a crash. It’s a correction from “unhinged fantasy” to “maybe slightly optimistic reality.” The technology is real. The applications are coming. The transformation of industry is happening .

But the idea that a handful of companies could spend unlimited amounts on infrastructure, depreciate it over geological timescales, and expect valuations to reflect “vision” rather than “earnings”—that idea is what just lost $1.3 trillion of value in six weeks .

The AI giants aren’t going away. They’re just discovering what every other industry learned long ago: eventually, you have to sell something for more than it costs to make it. And in 2026, with competition exploding and costs refusing to stay buried, that’s proving to be a surprisingly difficult problem for companies that thought they’d already solved the future.

Correction: An earlier version of this article suggested that AI companies might need to generate actual profits to justify their valuations. Readers have pointed out that this is “so 20th century” and that we should “trust the vision.” We regret the error—but we’re leaving it in, because apparently $1.3 trillion in losses is also just “vision materializing differently.”