By Crispin Woebegone, Senior Columnist for Intellectual Property & Indignation

7th January, 2026

In a shocking, unprecedented, and frankly heroic turn of events, The New York Times Company has been forced to take the drastic step of filing a lawsuit. Against whom? Against a cabal of Silicon Valley bandits who have committed the most brazen, daylight robbery of our age.

Their crime? Reading.

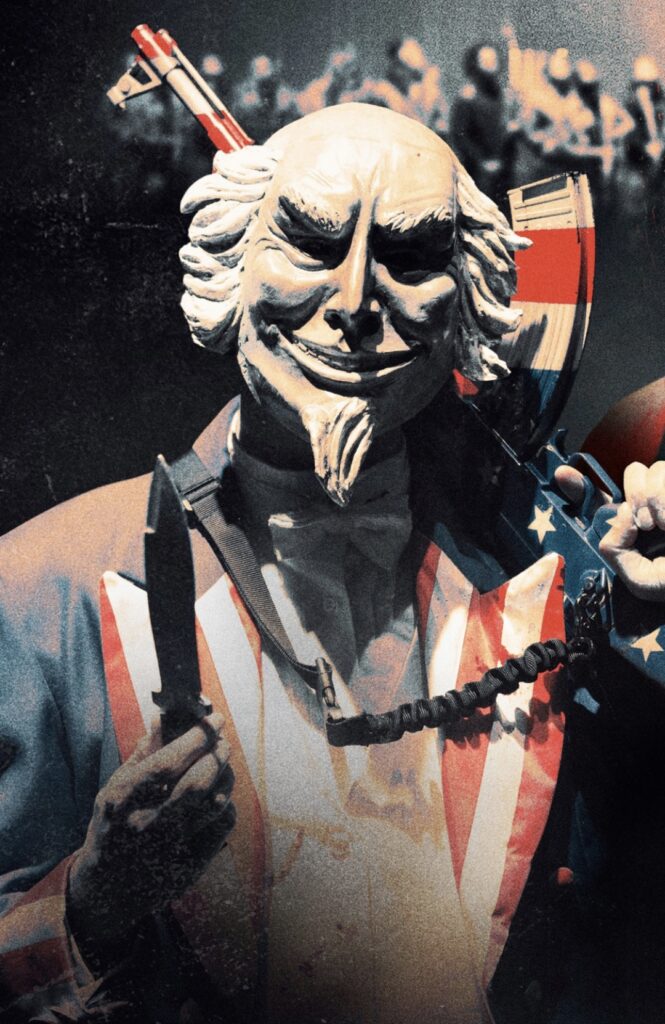

Well, “reading” in the way a hyper-advanced, trillion-parameter digital brain “reads.” The defendants, a little-known outfit called “xAI,” run by a notoriously publicity-shy recluse named Elon Musk, have allegedly—and we must use this legal term with appropriate gravity—infringed upon our copyrighted material. How? By using it to train their artificial intelligence models.

The audacity is breathtaking. For centuries, the hallowed journalistic process has been clear: reporters scour the world, braving dangerous Starbucks lines and treacherous subway delays to synthesize reality into prose. This prose is then published. The public may read it. They may be informed, enraged, or bored by it. They may even, in a fit of passion, discuss it with others. But what they may not do—and this is where xAI has allegedly gone full supervillain—is learn from it in a systematic, comprehensive way to build a machine that can summarize, discuss, or synthesize information itself.

We are not simply a “dataset.” We are not “training fodder.” We are The New York Times. Our sentences are not mere collections of words; they are meticulously crafted tonal arrangements, the intellectual property equivalent of heirloom tomatoes. The idea that some algorithm could ingest a report on municipal zoning disputes and then potentially generate a coherent paragraph on a related topic is not innovation. It is theft. It is the digital equivalent of a bookworm digesting a library and then having the gall to know things.

Mr. Musk’s company, in its typical flippant style, will likely argue something absurd about “fair use,” and “progress of science and useful arts,” or prattle on about how their AI “learns from the world” just as a human does. This is a false and dangerous equivalence. A human who reads the Times might gain insight. An AI that reads the Times becomes a competing purveyor of insight, and that is a line we simply cannot allow to be crossed. It’s one thing for a reader to be informed. It’s quite another for a machine to be smart. That’s our job.

Let’s be clear about what’s at stake here. If every two-bit AI startup can simply hoover up decades of investigative journalism, groundbreaking cultural criticism, and our famously witty wedding announcements to create ersatz intelligence, then what becomes of the model? The business model, that is. How will we fund crucial reporting on geopolitical crises if an AI can, hypothetically, answer a question about one? How will we sustain Style section think pieces on ankle boots if a machine can generate a lukewarm take of its own?

This lawsuit is not about clinging to the past. It is about defending the very ecosystem of truth. An ecosystem that, incidentally, has a very clear paywall and subscription structure. xAI didn’t just skip the paywall; they allegedly tried to disassemble the entire building to use our bricks for their own garage.

We stand at a precipice. Will we allow our collective digital memory—the first draft of history, written by us—to be copied, learned from, and built upon without proper compensation? Or will we stand firm and demand that intelligence, artificial or otherwise, must be licensed, siphoned, and metered appropriately?

The future of knowledge itself hangs in the balance. Or, at the very least, the future of its profitable dissemination. We see no difference. The lawsuit continues.